Are American Companies Fleeing China?

Exits rose across the board, but the heavyweight incumbents largely stayed put.

When do political risks necessitate divestment from a profitable market? That's the question boardrooms across the country are asking themselves in the wake of worsening U.S.-China relations over the last decade. As Beijing and Washington butt heads on national and economic security, the private sector has been caught in between.

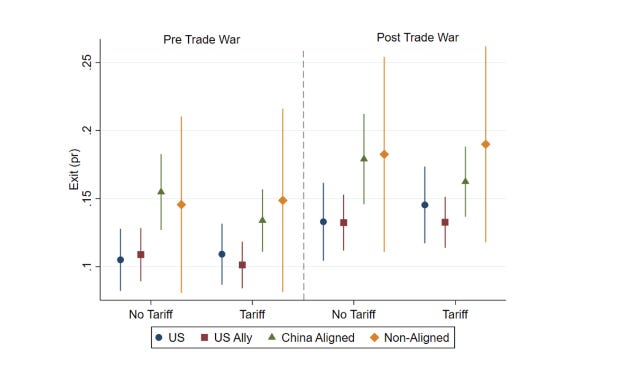

A recent paper by Samantha A. Vortherms (University of California, Irvine) and Jiakun Jack Zhang (University of Kansas) finds that exits among foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in China increased by about 3 percentage points, from slightly above 7% to slightly below 11%, during the trade war. They argue that the effects of the trade war were not as targeted as the tariffs themselves, with the increase in exits driven more by the blunt effect of political risk than firms from targeted industries and countries leaving. This suggests that tariffs may function more as a cudgel than a scalpel in shaping economic outcomes.

Researchers examined how President Trump's first trade war in 2018 impacted foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) in China, analyzing firm exit rates among all FIEs registered in China. They used the Foreign-Invested Enterprises in China (FIEC) Dataset, comparing the year before the trade war began (July 2017-June 2018) and the year immediately after (July 2018 to June 2019). An "exit" was recorded as any instance where a FIE reported its status to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce one year but not the next, treating a full closure, a sale of the company, or a subsidiary closure as equivalent forms of exit.

They found that U.S. firms in industries with higher tariffs were 1% more likely to exit China than international counterparts. Tariffs had no significant effect on the exit rate of U.S.-allied firms, with tariff-exposed firms no more nor less likely to leave than those not within the targeted industries. U.S. firms that are exporters had a lower rate of exit than the average U.S. firm, suggesting that these companies were able to use China's large domestic market to avoid the consequences of protectionist policy from Washington.

Researchers also found that the more registered capital a firm had, the less likely it was to exit. This suggests that firms with long term presence in China were less likely to leave the market, even in the face of tariffs. Firms that operated in China for only a few years were significantly more likely to exit, with firms established just one year before the trade war having a roughly 20% chance of exiting entirely. The least likely firms were those that had entered China during its initial entrance into the World Trade Organization in 2001, supported by nearly two decades of operational infrastructure.

Overall, the findings show that the trade war of 2018 led to a significant increase in firm exits, but these effects were not precisely targeted. Industries and countries specifically targeted with tariffs did not experience a substantial increase in exit rates beyond the broader, blunt effects of the trade war itself. Moreover, the ability of firms to withstand increased political risk depended heavily on their degree of entrenchment within the local market, with larger and more established firms being significantly less likely to exit compared to smaller, less entrenched entities. Thus, while smaller, less-entrenched firms may be pushed out by souring U.S.-China relations, the same cannot be said for the often larger and more entrenched firms that constitute the bulk of foreign investment.