Can Foreign Investment Shape a Country's Trade Policy?

What 180,000 foreign investment projects reveal about corporate influence

We know that large corporations have a significant impact on politics in their home countries, and an important aspect of globalization is that these corporations invest in projects overseas (referred to as foreign direct investments or FDI). But how do these corporations influence the countries they invest in? In Song Kim (MIT), Steven Liao (UC Riverside), and Sayumi Miyano (University of Osaka) investigate this question in a recent paper that examines how FDI impacts host countries’ trade policy.

The article proposes two arguments. First, the influence of large corporations causes the host country’s trade profiles (what the country imports and exports) to change. Specifically, host countries will expand trade in sectors and products directly related to FDI investments. Second, changing trade profiles will create new political coalitions of large multinational corporations (MNCs) and their suppliers. These coalitions can then lobby governments for trade policies beneficial to them.

MNCs and their political coalitions have economic leverage to lobby for beneficial policies because they create job and wage growth, use upcoming technologies, generate tax revenue, and donate to political organizations. This is especially true when corporations have long sustained projects in host countries with a deeper network of relationships between partners and local governments. As these corporations continue to invest and widen their network, the authors suggest that the host countries will adopt liberal policies that benefit MNCs by lowering trade barriers.

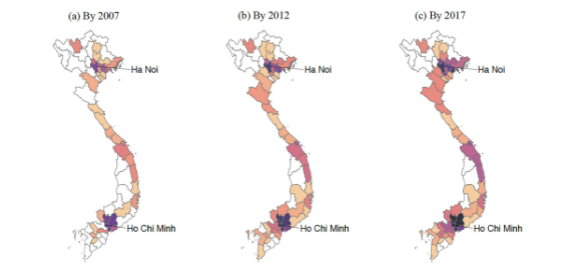

Using data from over 180,000 FDI projects in over 100 countries, the authors show that greenfield projects resulted in an average of 45 additional unique exported products one year after the start of a greenfield foreign direct investment project. Outside of global trade data, the paper takes a closer look at Vietnam due to their accessible firm-to-product data. Using this data, the authors found that, from 2003-2017, products related to FDI experienced a 90% increase in export volume within the first four years of a project starting, while import volume increased by 30%. These findings reflect how FDI from Samsung and Intel in Vietnam increased trade related to electronics production, shifting the economy away from a reliance on natural resources.

To address the author’s second assertion that reconfigured trade profiles will empower new political coalitions, they examine the relationship between Vietnam and South Korea. Using data from the 2015 Free Trade Agreement between Vietnam and South Korea, the authors find that products linked to greenfield projects received 19% and 30% larger import tariff cuts compared to non-FDI related products. This supports the theory that the countries trade profiles will not only adjust to FDI related products, but that host country governments will allocate resources in a way that benefits these corporations.

This study contributes to our understanding of globalization by showing that FDI impacts both home country and host country politics. Using global data and Vietnam’s firm-to-product level data, the authors find that FDI reshapes host countries trade profile and, consequently, trade policy. These findings suggest that future FDI studies should not only focus on the home country but continue to reveal how corporations impact politics beyond their own borders.