China's Belt, America's Chips, and the Economics of Strategic Leverage

The economic mechanics behind modern geopolitical coercion

Global superpowers use their economic strength to extract resources and gain power from other countries around the world. Though not as direct as the threat of war, countries like the US and China coordinate threats such as mark-ups, tariffs, and sanctions as a means of enforcement on foreign entities over which they have no legal jurisdiction. For example, in the race to get ahead in AI, the Biden Administration enacted a set of export controls designed to restrict China’s access to semiconductors and related technologies. More recently, on October 9th of this year, the Trump administration issued sanctions on Iran’s energy exports, aiming to protect America’s oil producers. This practice of leveraging economic power, known as geopolitics, is undoubtedly prevalent in today’s world. However, the larger question of how superpowers coordinate threats, and the outcomes they yield, has remained under explored.

A 2023 paper by Christopher Clayton (Yale), Matteo Maggiori (Stanford), and Jesse Schreger (Columbia) builds a formal model that provides a framework for understanding where geopolitical power originates from and how a hegemon (a dominant country, e.g. the US or China) wields it. The researchers hypothesize that the source of the hegemon’s power lies in its ability to coordinate threats across multiple economic channels. In other words, by linking sanctions or restrictions together across multiple sectors affecting the same country/firm -- what they call joint threats -- powerful countries like the US or China can more effectively enforce their demands.

Clayton et al. explain this through an intuitive framework: A network of firms and countries are connected by trade and finance. Within this network, actors must choose the degree to which they cooperate or deviate from other entities’ demands. Hegemons, which wield the power to enforce demands, form quid pro quo arrangements for firms, in which firms yield a better outcome by complying with the hegemon’s wishes than by rebelling. The hegemon exploits this dynamic by utilizing trigger strategies, which punish foreign entities who deviate from these quid pro quos by cutting off or inhibiting access to strategic goods and services. In practical terms, these joint threats often tell firms and governments: “If you don’t comply with our wishes, we will cut your credit and ensure our domestic firms stop buying from you.” Firms are thus incentivized to comply with these demands, as the cost of disobeying the hegemon’s wishes tends to supersede temporary losses in profit. By coordinating punishments along as many relationships among strategic sectors as possible, the hegemon seeks to maximize their Micro-Power (the maximal private cost to the entity the hegemon can demand). Subsequently, the hegemon’s social power (i.e. national security or strategic positioning within a given industry) also increases, maximizing their Macro-Power.

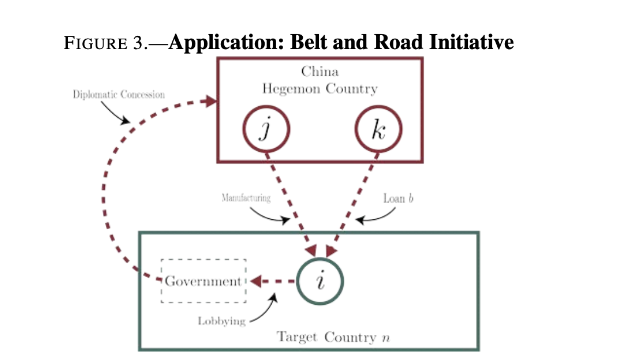

The researchers found that while the hegemon’s role as a global enforcer can mitigate some market failures, it “destroys value at the global level by demanding transfers and manipulating the equilibrium in its favor.” Clayton et al. ground this finding in relevant examples. For instance, in 2023 the United States demanded European firms and governments stop using information technology infrastructure produced by China’s Huawei due to concerns regarding its potential spying or military applications. In doing so, the US increased its Macro-Power but destroyed global value by denying other actors the gains from adopting the technology. Similarly, China’s Belt and Road Initiative has offered official loans and manufacturing relationships in exchange for political concessions, such as demanding countries do not recognize Taiwan as a legitimate state. In exchange, developing countries increase their borrowing capacity, while China’s increase in Macro-Power yields generous political surpluses.

In a geopolitical climate dominated by powerful interests, hegemons can use their economic strength to pursue geopolitical and economic goals. In the hegemon’s pursuit to maximize their security, strategic placement in key industries, and economic success, it increases its social value and global dominance. However, having extracted gains from firms and governments alike, the hegemon shifts the global equilibrium in their favor, destroying overall global value. By investigating international relations through this framework, we may be able to better understand the effects that dominant countries’ global policies have on communities and businesses alike.