How Neutral Countries Filled an $800 Billion Trade Vacuum

Replacing U.S.- and China-made goods became a global race — with uneven results.

During the US-China Trade War, trade flows around the world shifted. The sudden conflict, which began in 2018, upended a decades long trend of lower trade barriers and raised key questions about the response of bystander countries. Which countries met the new demand from the United States and China? And importantly, did those countries simply reallocate their exports from other countries to the U.S., or did the trade war create entirely new export opportunities?

According to a recent paper by Pablo Fajgelbaum (University of California, Los Angeles), Amit Khandelwal (Yale University), Pinelopi K. Goldberg (Yale University), Patrick J. Kennedy (University of California, Berkely), and Daria Taglioni (World Bank), the start of the US-China trade war was not, in fact, a turning point in the era of globalization. Contrary to common belief, rather than reducing global trade connectivity, the average country actually increased their global exports of tariffed products. However, the degree to which they did so varied significantly from country to country.

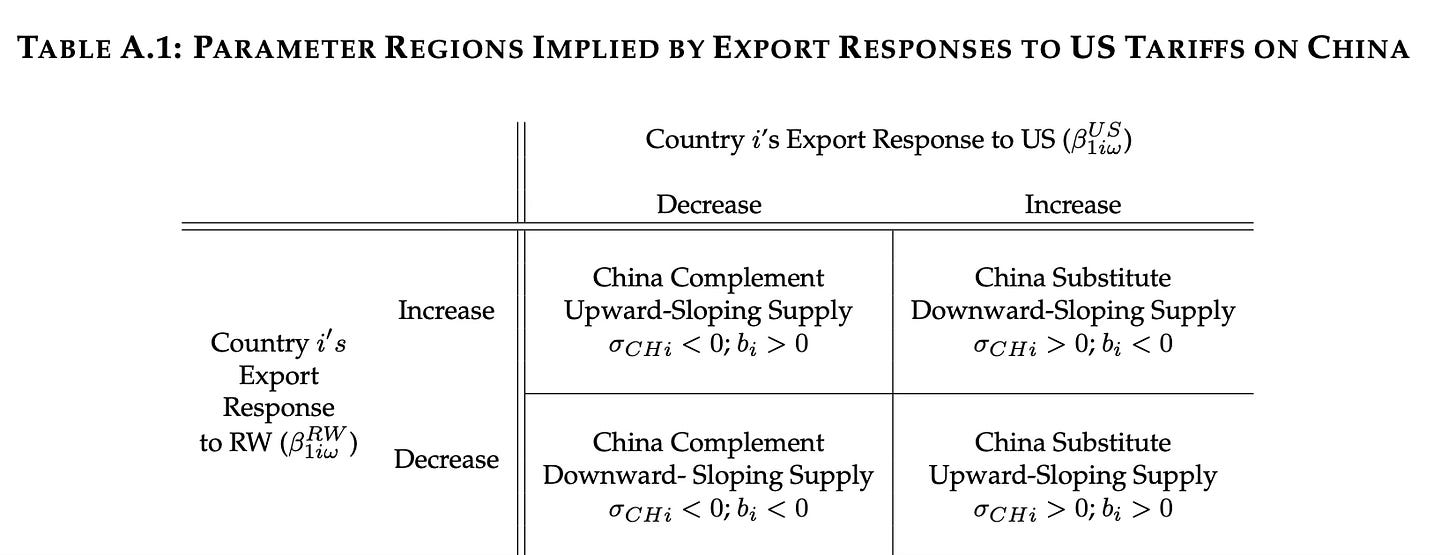

The researchers theorized that this disparity had to do with two specific attributes of each country: whether they produced goods that could function as a replacement to the taxed American and Chinese goods, and whether they were able to rapidly ramp up production to meet new demand. Countries with both of those characteristics would benefit the most from the conflict, and countries that produced goods that were generally used alongside American and Chinese goods would be harmed by the conflict.

The team analyzed data for 5203 products, split into 3 separate 2-year periods, -- 2014/15, 2016/17, and 2018/19 -- sampled from the top 50 exporter countries (excluding oil exporters). The team’s sample contained 95.9% of global trade, or 70.5% if excluding the US and China. They separated the exports by destination, (US, China, or the rest of the world), and further classified each export into one of nine different product categories.

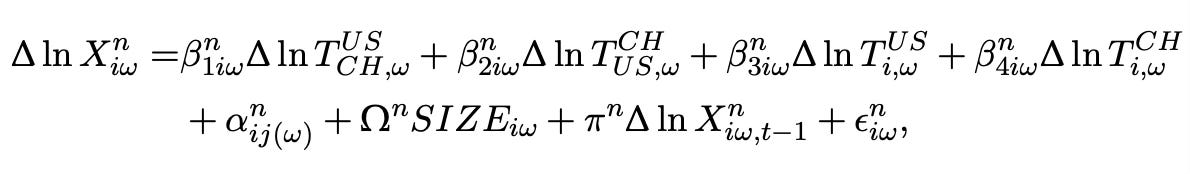

To analyze the data, the team estimated a rather complicated looking formula that predicts the change in a country’s exports using the impacts of tariffs from the US and China on each other and bystanders, as well as the original size of the trade flowbetween the country and the US, China, and bystander countries, and a few control variables.

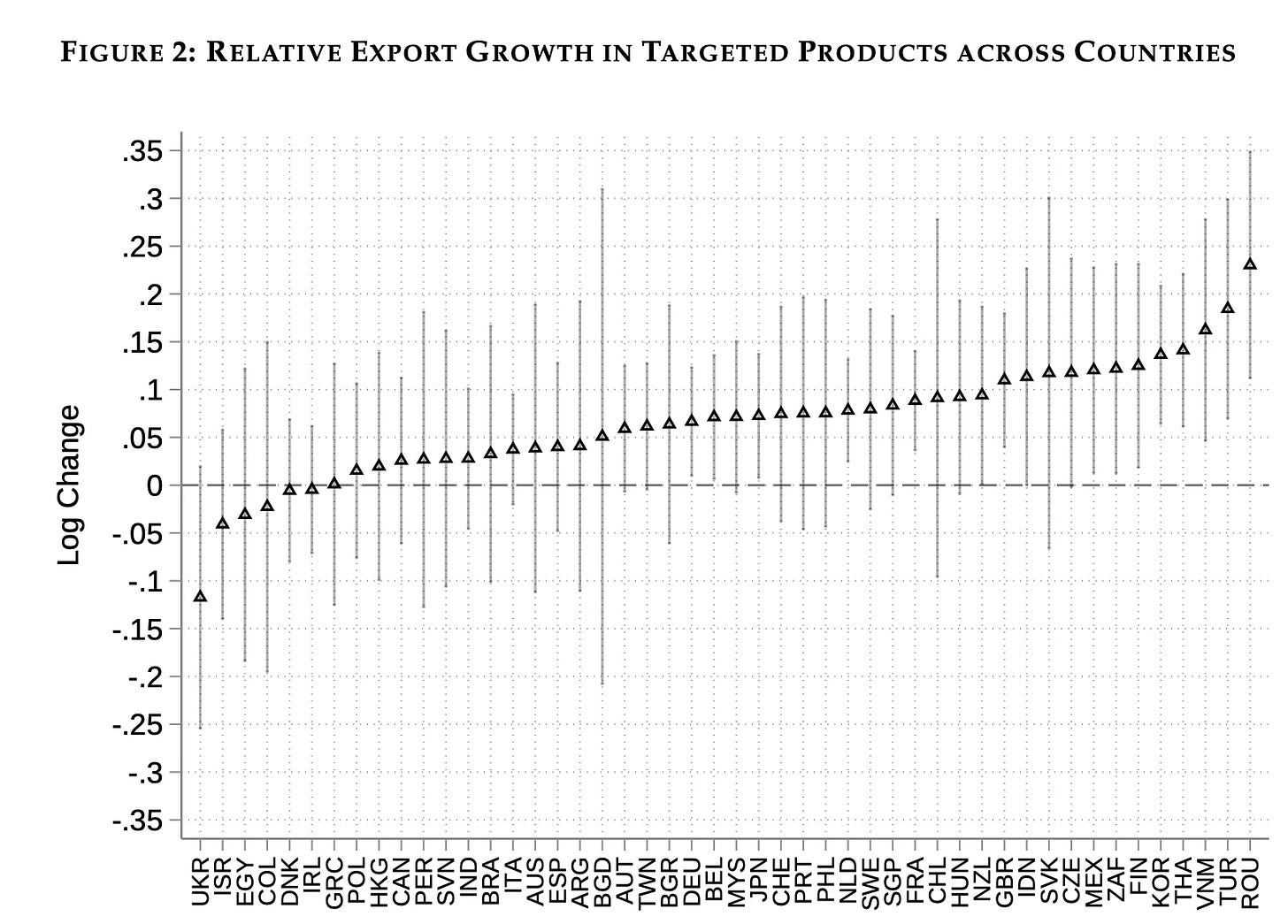

The evidence suggests a few key takeaways. First, the escalation of tariffs did not just redirect trade, but also created more net exports from third countries. Second, using an average to determine the effect on global trade masks vast differences in export change across countries. For example, nations such as Thailand and Mexico grew their exports, but Ukraine’s exports shrank. Third, the change in a country’s exports was not due primarily to a country’s prewar specialization, but rather country-specific components, such as whether the country’s goods could effectively function as a replacement for US-China goods, whether the goods were generally bought alongside Chinese and American goods, and how easily the country was able to ramp up production.

Overall, the paper shows that the trade war did not constitute a major turning point in the era of globalization. Exports from many countries actually increased during the trade war. A nation’s ability to increase production and whether its goods were bought alongside or as a replacement to Chinese or American goods are the primary factors behind whether a nation increased or decreased its net exports. Rather than bringing an end to the era of globalization, the trade war showed the strength of global trade. Trade to the US was not shut off, but rather, shifted.