Mapping Beijing's Economic Pressure

A new dataset reveals patterns in Chinese sanctions behavior

Recent research on China’s trade strategy suggests the CCP increasingly relies on coercive trade restrictions to achieve foreign policy goals. Data collected by the Trade War Lab confirms a significant uptick in sanctions imposed by China since 2018. Other scholars have also documented the distinctive methods China uses to sanction countries. A prime example of Chinese economic coercion came on October 17th, 2025, when China announced major sanctions against South Korea’s Hanwha Ocean, the largest shipbuilder in the world, that specializes in Liquified Natural Gas, Crude Oil, and Gas carriers. The sanctions specifically target Hanwha subsidiaries that support U.S shipbuilding efforts, with the goal of muddling Hanwha’s business dealings with the US. Through these undertakings, China is sending a clear message: you have been warned, if you choose to undermine our geopolitical interests, proceed at your own risk. Beijing’s tendency to use sanctions like these makes knowing when, how, and why China uses economic coercion important to understanding US-China relations.

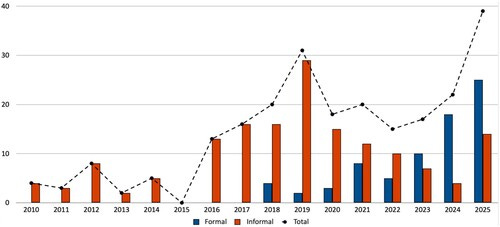

China’s use of economic sanctions is further explored in a new paper and corresponding dataset, by Viking Bohman (Tufts University), Audrye Wong (University of Southern California), and Victor Ferguson (Hitotsubashi University). The authors document over 200 individual sanctions imposed by China between 2010 and 2025. The dataset tracks both “informal” and “formal” sanctions, relying on official Chinese websites to identify formal sanction activity, and aggregating media reporting, timing, and international interpretation of China’s actions to track informal sanction measures.

The authors argue that their dataset captures two key trends. First, despite a long history of informal sanctions, formal sanctions by the CCP have been on the rise as a response to American economic coercion. Second, they claim that China’s new economic weapons are not a replacement for the CCP’s longstanding informal strategy, instead they represent an additional tool to bolster informal sanctions when needed.

Historically, China’s trade strategy has been largely informal. Instead of the CCP taking overt, legal steps to institute sanctions, government officials worked behind the scenes to induce sanction-like behavior. The authors describe how Chinese officials encourageconsumer boycotts of multinational companies, discretely manufacture reasons for customs officials to delay or block imports, and unfairly target foreign businesses with technical violations of domestic regulation. These somewhat deceitful methods gave the CCP plausible deniability and allowed them to maintain their position that economic sanctions are an illegitimate tool of US hegemony without contradicting themselves. The authors note that China has enjoyed the results of being ambiguous and informal on trade decisions, keeping targets guessing, making it difficult for their western counterparts to respond accordingly.

However, Ferguson et al go on to describe the CCP’s shift to a more hybrid model in 2018. Since then, China has developed new formal tools for sanctioning, such as the Unreliable Entity List (a legal tool to impose restrictions on foreign companies, organizations, or individuals, who are deemed a threat to National Security), anti-foreign sanction laws, and an expanded set of export control systems. Figure 1 shows the corresponding increase in formal sanctions. While informal methods are still deployed when China values discretion, such as when the country seeks to minimize reputational costs or backlash from the target, formal methods are used as a statement, especially when it comes to top interests like Taiwan.

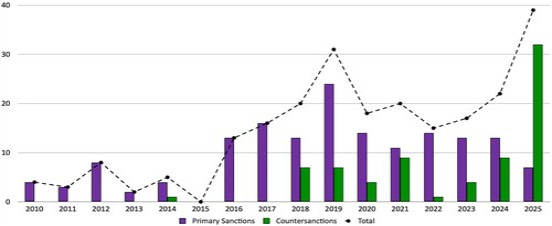

The research also finds that China has become increasingly willing to escalate conflict by imposing countersanctions. However, the CCP has also become less proactive, with data reflecting a downturn in the use of primary sanctions, and a distinct uptick in countersanctions.

The authors suggest China’s increasing preoccupation with responding to escalating US economic pressure has left the CCP with less capacity to target others.

In a time of extreme levels of trade coercion and risks of large-scale economic decoupling, it is clear Beijing has begun to recalibrate their approach to trade. The country is shifting from proactive to reactive, and obscure to defined. Beijing knows that their geopolitical leverage has increased dramatically over the years, and now they can draw lines in the sand when desired. The dataset presented by Ferguson et al elucidates China’s shadowy trade strategy, allowing policymakers to better understand and deploy effective responses.