The Politics of De-Risking

As Washington and Tokyo tighten controls on trade with China, their approaches reveal both shared anxieties and strikingly different priorities.

It’s no secret that over the past century, China has emerged as a new global economic superpower. To combat its rising influence, countries have shifted their economic strategies from engagement to “de-risking”. Specifically, countries such as the US and Japan are transitioning to economic policies that view China through a more hostile lens. Since the beginning of the US-China Trade War in 2018, the US has taken an increasing number of protectionist measures in the name of protecting national security. On the other side of the world, Japan has also begun enacting securitizing policies, targeting specific goods for de-risking. It is important to understand the reasons behind how these countries are tightening their grip on multilateral trade.

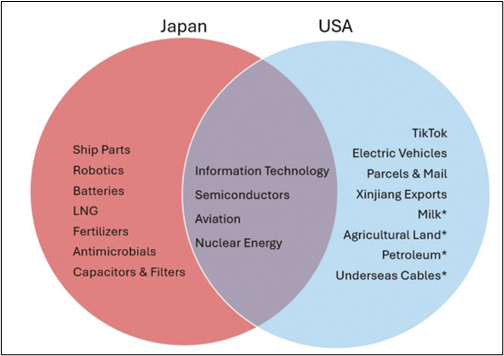

A recent paper from Timothy Cichanowicz (University of Kansas) and Jack Zhang (University of Kansas) analyzes the legislative responses of the US and Japan, China’s two largest trading partners (excluding the EU), to de-risking with China. The paper found that both the US and Japan placed significant importance on securitizing information, semiconductor, aviation, and nuclear energy technologies. Despite these similarities, the differences in the US and Japan’s political, economic, and environmental spheres mean that many other trade policies in the two countries diverge. These differences imply that although both countries may appear to be moving towards de-risking, different countries are bound to de-risk in different ways.

By looking at the legislative measures taken by the US and Japan from 2018-2024, the authors are able to analyze the underlying motivations behind this transition to “de-risking”, which Cichanowicz and Zhang define as “the middle ground between engagement and decoupling.” They gathered 166 “tough on China” bills written by US lawmakers from 2018-2024, mostly from Republican lawmakers. Ultimately, 13 of them passed through at least one chamber of Congress without becoming law, and nine became law or eventually had parts passed in other bills that became law. The number of these bills limiting trade with China modestly increased from 2018-2022, but then increased tenfold in 2023, marking escalating de-risking legislation within the US.

On the other hand, Japan passed many fewer, more focused bills than the US. In May of 2022, the Japanese Diet approved the “ESPA” (Act on the Promotion of National Security through Integrated Economic Measures). This bill lays out a framework for securitizing materials strategically important to Japan. Certain qualifying criteria decide whether future materials need to be securitized. For example, a resource may be securitized if it is: (a) Necessary in everyday life, (b) extremely dependent on overseas suppliers, (c) subject to supply chain disruptions, or (d) key to stability. The Japanese House of Chancellors has already designated a 1,035.80 yen budget for the eleven materials securitized by ESPA’s criteria.

The US and Japan’s approach to de-risking with China differs in a few important ways. Mutually shared geopolitical concerns, such as microchips, semiconductors, information and cloud-based technologies, airplane parts, and uranium fuel, are heavily featured in the legislative discourses of both countries. However, Japan’s securitization is mainly influenced by its concern about access to scarce resources. On the other hand, the US bills securitize products with minimal links to national security, such as its legislation to ban TikTok, a popular social media app. Additionally, compared to Japanese legislation, US bills more often directly mention China as a threat to US economic security, while Japanese bills don’t directly mention China once. Not only are Japan’s bills less direct about China being an economic adversary, but they also have a much smaller budget than US bills. The aforementioned ESPA bill set aside less than 10 billion USD for the 11 securitized products, while the US’s Chips and Science Act (channels federal funds to support the domestic manufacturing of semiconductors) alone is funded by over 50 billion USD.

One possible implication of this convergence of economic strategy between the US and Japan is that there is an increasingly important global de-risking trend that converges on some specific products. Another possible outcome of this convergence in strategy is global agreement on the necessity of securitizing said products, which may contribute to global supply chains shrinking. Complete decoupling from China is very unlikely, however. Finally, as the US enacts more and more protectionist policies, the line between protectionism and genuine interest in national security begins to blur. Modern democracies must learn to find the balance between economic security and economic freedom in today’s unpredictable world.