What If the Public Controls Sanctions More Than We Think?

New research upends the conventional wisdom that foreign policy belongs to elites alone

Following Russia’s deployment of troops into separatist regions as part of the larger invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Noel Quinn, the former CEO of one of Europe’s largest banks, HSBC, commented on the European Union’s discussion of establishing more sanctions. Quinn described the fallout of sanctions as a “contagion” that would spread to banks with ongoing operations with Russia. Other banks described the effect of the potential sanctions as an “escalating conflict,” having “major consequences.” Such descriptions no doubt aim to shift public opinion against sanctions, begging the question: does public demand for economic sanctions exist, and what factors inform such demand?

A recent study by Cora Caton (University of Maine) and Clayton Webb (University of Kansas) offers insight into the relationship between public perceptions and sanction politics. Caton and Webb’s “A Public Demand Theory of Economic Sanctions” posits that the more a sanction is reported to cost, often communicated as abstract terms via national media, the less it is demanded by the public. Demand is also significantly shaped by the perceived importance of the inciting international event. If an initial event is perceived to be important, it increases the demand for its subsequent sanctions regardless of how costly they are perceived to be. The researchers further show that imposing sanctions without public support can reduce politicians’ approval. Such findings challenge the common notion that the public holds no sway over foreign policy.

The authors argue that most people are not directly impacted by sanctions; therefore, their understanding of cost is based on sanction’s perceived impact on their community and the nation more broadly. This perception is often derived from abstract media framing. In turn, perceived cost, or how high the economic consequences are reported to be, shapes the demand for sanctions. Alongside shaping perceptions of cost, media influences how important the public considers the inciting event to be. Demand only exists when there is enough media coverage to establish “significant public awareness,” in other words, the kind of coverage afforded mostly to major international events concerning interests of security and territory, rather than trade. As a result, there is increased public willingness to support economic sanctions for highly covered issues such as security.

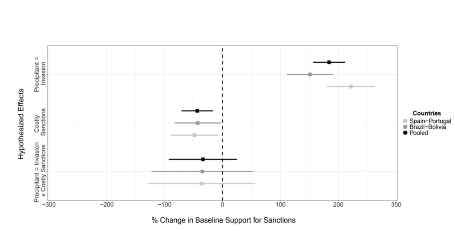

To test this theory, researchers conducted a survey experiment in which participants were placed in eight groups that were then each exposed to a passage describing a different sanctions event. These passages varied based on three factors: a precipitant event of high versus low importance, media coverage of costs versus no coverage, and conflict between European versus Latin American countries. Participants were then asked whether they supported the sanctions, as well as if they approved of the performance of the president in the paragraph they read.

The results ultimately supported the theory posited by the researchers. Participants were between 42.9 and 48.6% less likely to support economic sanctions when told sanctions would negatively impact the economy, and between 151 and 222% more likely to support the establishment of sanctions if they were in response to territorial conflict. When respondents were given passages that mentioned both the territorial conflict and the cost of the sanctions, costs reduced support for security-related sanctions by approximately the same amount as when the conflict was described as trade related. In other words, the effect of the inciting event on support for sanctions was not conditional on cost.

The results of the participant’s evaluation of the president’s performance were consistent with the pattern of demand described above. When cost was mentioned, presidential approval decreased with demand, and if the precipitant event was an invasion, approval increased with demand. Thus, sanctions had a tangible impact on the perception of presidential performance.

Caton and Webb’s research provides a lens through which to view public demand for economic sanctions. Central to this argument is the finding that public demand for sanctions is inversely related to its perceived economic cost. When sanctions are reported by the media to produce higher costs, public support diminishes. Precipitant events deemed crucial, expressly those related to security, bolster willingness to support sanctions regardless of cost. Such a dynamic suggests that, while costs dampen sanction support, people’s perception of the inciting event as important offsets this effect equally across all levels of cost. Finally, the authors show that imposing sanctions when support is low harms presidential approval. Such findings suggest that the public does care about foreign policy, meaning the decision to impose sanctions may have a discernable effect on domestic politics.