Why Tariffs Haven't Broken Supply Chain Ties

Chinese supply chains remain deeply embedded in U.S. imports

Since 2018, the United States has led efforts to reduce its dependence on Chinese products by imposing tariffs and diversifying its imports. These policies aim to “decouple,” or disconnect, the two countries’ economies. However, rather than reshoring production, these policies have resulted in a reorganization of supply chains. Other countries, some closely linked with China, have filled in the gaps created by the tariffs by exporting to the United States. In fact, contrary to public rhetoric suggesting trade tensions cause deglobalization, trade flows have remained relatively high since tariffs were imposed. This reshuffling of international trade presents an important question: to what extent are these tariffs achieving decoupling from Chinese supply chains, versus circuitously reshaping global interdependence?

According to a recent paper by Caroline Freund (UC San Diego), Aaditya Mattoo (World Bank), and Michele Ruta (IMF), tariffs imposed during the first Trump and early Biden Administrations reduced China’s share of U.S. imports by six percent. They noted that bilateral trade has decoupled significantly; however, supply chains are still interconnected with China. In fact, the fastest growth in U.S. trade has occurred between countries that maintain intensive intra-industry trade with China in strategic sectors. This suggests that production networks are adapting to the tariffs, raising broader questions about the effectiveness of trade policy as a tool for decoupling.

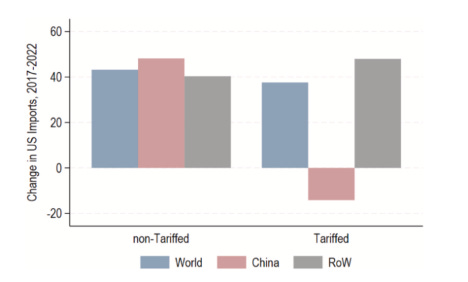

The researchers examined the characteristics of countries replacing Chinese imports to predict which states benefited the most from the tariffs. Using difference-in-difference analysis, the authors compare the growth of trade in tariffed products versus non-tariffed products from China versus the Rest of the World before and after the beginning of the trade war. This allowed them to separate the effect of the tariffs from other trade shocks.

Ultimately, the authors found that US imports from China of tariffed goods grew 40% more slowly than imports of tariffed goods from other countries. The countries with the biggest gains in import share were Vietnam with a 1.9 ppt increase, Taiwan, Canada by 0.8 ppts, Mexico with 0.6 ppts, India at 0.6 ppts, and Korea with a 0.5 ppt increase. These results suggest the tariffs encourage nearshoring and friendshoring. Nearshoring is relocating production to close countries (Mexico), and friendshoring is shifting production to allied nations or strategic partners (Vietnam).

Although they find evidence of increased trade connectedness with friendly countries, the authors show that countries with existing supply chain linkages to China have seen the fastest export growth. They found that, from the 25th to the 75th percentile of countries linked to China, there was a 4.2% increase in strategic goods that were exported to the United States. In particular, South Korea and Thailand replaced Chinese imports in strategic industries.

This research shows that tariffs do not always achieve decoupling as expected. Bilateral decoupling is possible, but using tariffs to completely decouple is challenging. U.S. imports have diverted from China to its close trade partners. This keeps the U.S. integrated in Chinese supply chains and, in some strategic industries, even strengthens linkages. These dynamics left the United States reliant on Chinese supply chains during the beginning of the trade war, while the effect of the Trump Administration’s newer tariffs remains to be seen.