Assessing the Costs of America’s Protectionist Turn

Tracing back trade expansion

The tidal wave of tariffs emerging from the White House has spurred American businesses across the country into “survival mode.”1 While continued temporary pauses have provided some respite, the overbearing pressure threatens to squeeze everything from local mom and pops to multinational corporations. As the summer months have come and gone, we are now witness to the increasingly visible economic fallout, with a dismal July jobs report showing the first signs of strain.2 The backlash against free trade has real causes: concentrated job losses, weak adjustments, and perceived unfairness. Yet research gives little support to the idea that sweeping tariffs will restore what was lost.

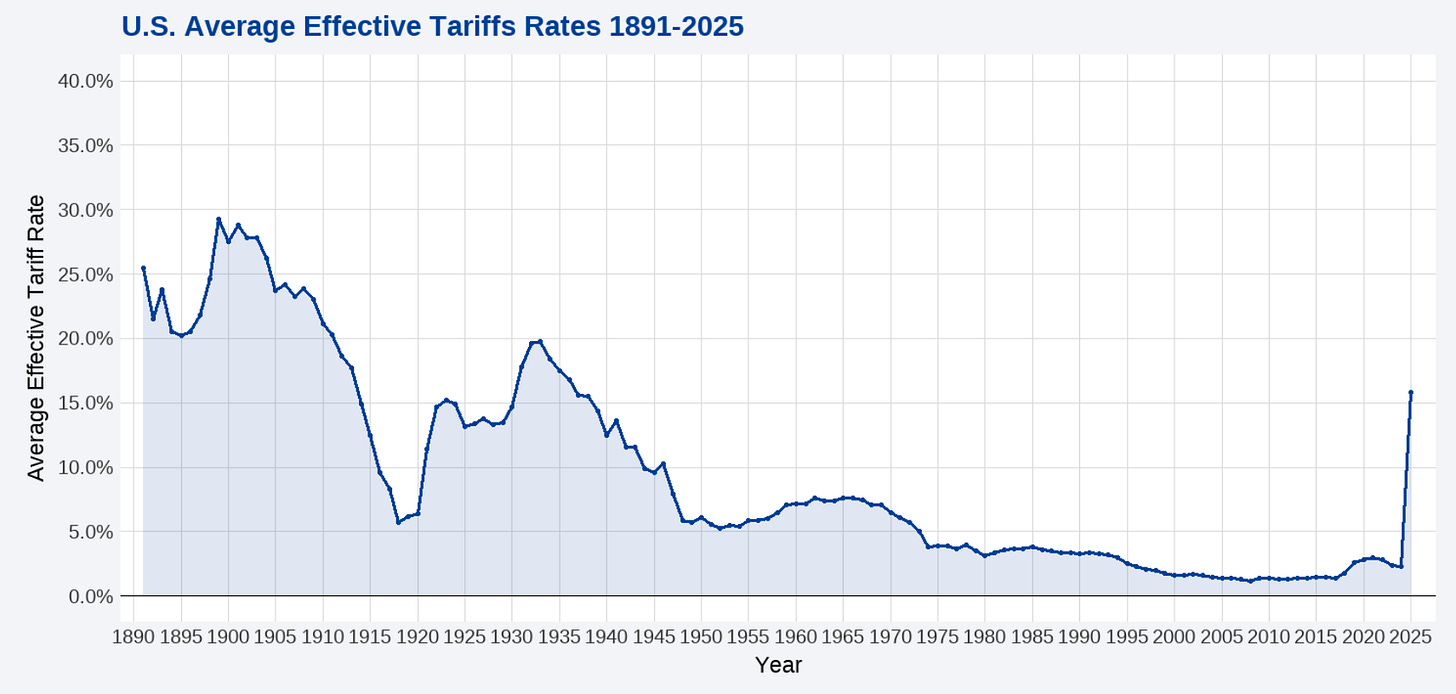

Since the conclusion of World War II, the United States has brandished expanding trade as the key tool to foster global economic growth, integrate markets, and reinforce a U.S.-led international order. Tariffs steadily fell throughout each ensuing decade until reaching their resting place at around 1.5% in the 2000s.3 This market access was accompanied by historic increases in the flow of trade; imports surged from under $500 billion annually in the 1970s to nearly $4 trillion by 2023.4 Both parties embraced the idea that open markets supported growth, efficiency, and American leadership in the global economy. However, with Trump’s entrance into office in 2016 and the subsequent start of the trade war in 2018, the political paradigm has shifted towards protectionism.

The increase in the average tariff rate from 1.8% to 2.8% during the trade war marked the largest spike in tariffs since 1957–1959, which experienced a 1.1 percentage point jump.5 Rhetoric around free trade continued to shift after Trump left office, as the Biden administration avoided rolling back duties on Chinese goods and expanded efforts to protect and invest domestically in critical industries.6 Then came Trump’s reelection and liberation day, when Trump announced a comprehensive list of tariffs on trading partners ranging from a base of 10% all the way to 50%.7 This announcement sparked escalatory tit for tat increases from countries like China. As of August 1st, the new effective tariff rate rests at 15.8% — an increase of nearly 7-fold in one year or 13.5 percentage points — marking the highest tariff rate seen by consumers and businesses since 1937.8 Trump’s trade barriers outpace the disastrous Smoot-Hawley tariffs, which only produced a 6.3 percentage point rise in rates over a 5-year timeframe.9

THE FALLOUT OF TRADE EXPANSION

Trump has argued since the 1980s that free trade hollowed out U.S. manufacturing, and his tariff agenda is being presented to correct those historical wrongs. “How could anybody have signed a deal like NAFTA,” he declared in 2018, capturing the widespread sense that earlier trade agreements had devastated local industries.10 NAFTA also faced opposition when it was passed, mostly from the left. In the House, NAFTA passed 234–200, with 156 Democrats opposed.11 Recent research on NAFTA confirms why these concerns resonated. Although national studies typically found little or no aggregate welfare impact, new county-level analysis shows that regions reliant on labor-intensive industries experienced large and persistent employment losses after the agreement took effect.12 The hardest-hit areas were disproportionately low income, less educated, and concentrated in the South, where job losses deepened existing inequalities. Adjustment programs like Trade Adjustment Assistance provided some relief, but the scale was minor compared with the magnitude of employment declines.13 What looked like a null effect for the nation masked serious localized costs.

After 2001, these patterns intensified dramatically with surging Chinese imports. Autor, Dorn, and Hanson’s 2013 paper showed that regions most exposed to Chinese competition in furniture, textiles, and electronics endured steep employment declines, wage stagnation, and increased reliance on safety nets.14 In many cases the same industries and communities that had already been battered by NAFTA were hit again, only now on a much larger scale. Statistically, the China Shock quickly overshadowed NAFTA’s impact, but this did not mean the earlier damages halted; they were simply folded into a broader national wave of disruption. What began as geographically concentrated costs under NAFTA transitioned into a full-scale assault on national manufacturing labor markets, with devastation hitting the most vulnerable communities. Although later work found that some local economies eventually stabilized, the original displaced workers rarely regained their prior earnings or positions.15

CONSEQUENCES OF SHIFTING POLICY

These diagnoses of the harm from free trade carry weight, but the remedies being pursued may come with their own costs. Academic research on the trade–growth nexus has evolved considerably over the past half century. Early studies produced mixed results, with some suggesting that export growth spurred development, while others argued domestic strength had to come first. More recent work, however, has sharpened the methods and shows more consistently that trade supports growth, though the channels vary.16 Large cross-country and panel studies from the 1990s onward find that openness is associated with faster productivity growth and rising incomes, much of it transmitted through increased investment and the ability to obtain new machinery, equipment, and technology from abroad. Trade also raises incomes by expanding markets, which allows countries to sell more of what they are most efficient at producing. Finally, trade promotes the spread of knowledge across borders, giving firms and workers access to new techniques and ideas that build skills and, over time, support long-run innovation.17 These claims are not without contention, critics such as Rodriguez and Rodrik (1999) caution that many measures of trade openness are closely tied to broader indicators of economic stability, raising doubts about whether trade itself drives the observed growth effects.18

The process of development from trade differs depending on a country’s stage of development and relative resources, labor capacity, and capital. At the microeconomic level, U.S. firms show a clear “self-selection” pattern, where only the most productive firms compete abroad.19 Firms already operating at high levels of efficiency and productivity can absorb the high fixed costs of entering foreign markets, while less efficient firms remain focused on domestic sales. Some developing economies, however, demonstrate “learning-by-exporting,” where cheap-labor incentivizes countries to enter labor-intensive export markets.20 Economies with lower wages can produce low-technology, labor-intensive goods for lower prices than developed economies that must pay higher wages, giving them an edge in these industries. For less developed countries, trade in low-technology goods may help build physical and human capital in the long run. Protectionism and subsidies may also benefit these countries as they develop fledgling industries, as was the case in South Korea.21 For the U.S. however, the learning-by-exporting channel is limited, as most industries lack the comparative advantage of cheap labor and are unlikely to be competitive exporters unless they are highly efficient. Instead, historical evidence shows that protectionism tends to create inefficiency by reducing competition and depressing long-run growth.22 Advanced economies such as the U.S. depend on innovation and capital-intensive efficiency in established industries.

Tariffs also directly raise prices for consumers, increase costs for domestic producers, and deliver only modest job gains. By making imported inputs like steel, aluminum, and batteries more expensive at home while foreign competitors continue sourcing them cheaply, tariffs often leave American businesses less competitive in global markets and raise prices domestically.23 These burdens extend well beyond the targeted goods. For example, a price increase on goods such as mattresses results in higher prices for goods bought alongside them, such as bedframes. Multinational firms frequently relocate production to sidestep tariffs, meaning tariffs relocate jobs, but not necessarily to the United States.24 Meanwhile, domestic producers often raise prices in parallel with tariffs, as they no longer need to compete with cheaper, imported goods.25

The 2018 safeguard tariffs on washing machines illustrate these effects. Washer prices rose nearly 12 percent, and dryers, though not subject to tariffs, increased by the same amount as firms across the industry adjusted pricing. With about 10 million washers and 7.7 million dryers shipped annually, consumers faced an added cost of roughly $1.55 billion each year. Although employment in the sector grew by about 1,800 jobs, the cost per job exceeded $800,000 annually.26

CONCLUSION

The U.S. is undergoing a sharp break from decades of free trade. The localized impacts from NAFTA and expansive devastation from Chinese import competition has left many Americans with a sour taste in their mouth, culminating in a desire to implement protectionist policies to bring back manufacturing. Ultimately, the evidence and literature around free trade and tariffs fails to show that broad protectionist surges reliably restore jobs or raise long-run living standards; instead, they consistently document higher consumer and input costs, modest and expensive employment gains, and slower productivity growth. While the diagnosis of the issue may be correct, the cure appears to be heavily misguided.

Wakabayashi, Daisuke. “Trump’s Tariffs Push U.S. Businesses into “Survival Mode.”” The New York Times, 20 Aug. 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/08/20/business/trump-china-tariffs-american-importers.html.

Carlson, Seth, and Vinny Amaru. “July Jobs Report Highlights US Job Growth Has Slowed Significantly; Markets React Negatively.” Chase.com, 4 Aug. 2025, www.chase.com/personal/investments/learning-and-insights/article/jobs-report-july-2025.\

U.S. International Trade Commission. U.S. Imports for Consumption, Duties Collected, and Ratio of Duties to Value, 1891–2023. Office of Analysis and Research Services, Office of Operations, May 2024.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. “Imports of Goods and Services.” FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 1 Jan. 1946, fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IMPGS.

U.S. International Trade Commission. U.S. Imports for Consumption, Duties Collected, and Ratio of Duties to Value, 1891–2023. Office of Analysis and Research Services, Office of Operations, May 2024.

Boak, Josh, et al. “Biden Hikes Tariffs on Chinese EVs, Solar Cells, Steel, Aluminum — and Snipes at Trump.” AP News, 14 May 2024, apnews.com/article/biden-china-tariffs-electric-vehicles-evs-solar-2024ba735c47e04a50898a88425c5e2c.

Harithas, Barath, et al. ““Liberation Day” Tariffs Explained.” Csis.org, 3 Apr. 2025, www.csis.org/analysis/liberation-day-tariffs-explained.

Morgan, J.P. “U.S. Tariffs: What’s the Impact? | J.P. Morgan Research.” Jpmorgan.com, J.P. Morgan, 2025, www.jpmorgan.com/insights/global-research/current-events/us-tariffs#section-header#0.

U.S. International Trade Commission. U.S. Imports for Consumption, Duties Collected, and Ratio of Duties to Value, 1891–2023. Office of Analysis and Research Services, Office of Operations, May 2024.

“Remarks by President Trump on the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement – the White House.” Trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov, 1 Oct. 2018, trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-united-states-mexico-canada-agreement/.

Gerstenzang, James, and Michael Ross. “House Passes NAFTA, 234-200 : Clinton Hails Vote as Decision “Not to Retreat” : Congress: Sometimes Bitter Debate over the Trade Pact Reflects Hard-Fought Battle among Divided Democrats. Rapid Approval Is Expected in the Senate.” Los Angeles Times, 18 Nov. 1993, www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1993-11-18-mn-58150-story.html.

Choi, Jiwon, Ilyana Kuziemko, Ebonya Washington, and Gavin Wright. 2024. "Local Economic and Political Effects of Trade Deals: Evidence from NAFTA." American Economic Review 114 (6): 1540–75.

Choi, Jiwon, Ilyana Kuziemko, Ebonya Washington, and Gavin Wright. 2024. "Local Economic and Political Effects of Trade Deals: Evidence from NAFTA." American Economic Review 114 (6): 1540–75.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. "The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States." American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68. DOI: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. "The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States." American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68. DOI: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x

Rodriguez, Francisco, and Dani Rodrik. “Trade Policy and Economic Growth: A Skeptic’s Guide to Cross-National Evidence.” National Bureau of Economic Research, 1 Apr. 1999, www.nber.org/papers/w7081.

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x

Haggard, Stephan, and Myung-Koo Kang. “The Politics of Growth in South Korea.” Chapter. In The Oxford Handbook of Politics of Development, edited by Carol Lancaster and Nicolas Van de Walle, 669–81. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x

Singh, T. (2010), Does International Trade Cause Economic Growth? A Survey. The World Economy, 33: 1517-1564. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01243.x ; Flaaen, Aaron, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot. 2020. "The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines." American Economic Review 110 (7): 2103–27. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20190611

Flaaen, Aaron, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot. 2020. "The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines." American Economic Review 110 (7): 2103–27. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20190611

Flaaen, Aaron, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot. 2020. "The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines." American Economic Review 110 (7): 2103–27. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20190611

Flaaen, Aaron, Ali Hortaçsu, and Felix Tintelnot. 2020. "The Production Relocation and Price Effects of US Trade Policy: The Case of Washing Machines." American Economic Review 110 (7): 2103–27. DOI: 10.1257/aer.20190611