Did Political Influence Determine Who Got Tariff Exclusions?

Researchers analyzed over 52,000 exclusion requests to test whether lobbying made a difference

For decades, scholars have debated whether corporate lobbying actually affects trade policy. While most agree it has an effect, finding a direct link remains difficult. Some historical tests, such as that of Grossman and Helpman (1994)1, suggest that lobbying does work to change policy. In another study, Lee and Baik (2010)2 show that firms that lobby more received higher Byrd Amendment payouts on antidumping duties. Even so, considering the widespread popular assumption that lobbying works, surprisingly little research draws a direct connection between lobbying and specific policy outcomes.

After the Trump Administration imposed steep tariffs on China in 2018, the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative created a process for firms to request tariff exclusions. Facing higher costs, some firms lobbied the USTR to improve their chances of approval. This process afforded scholars a unique opportunity to test whether lobbying works to gain exemptions. So, the question remains, did lobbying help firms secure tariff exclusions?

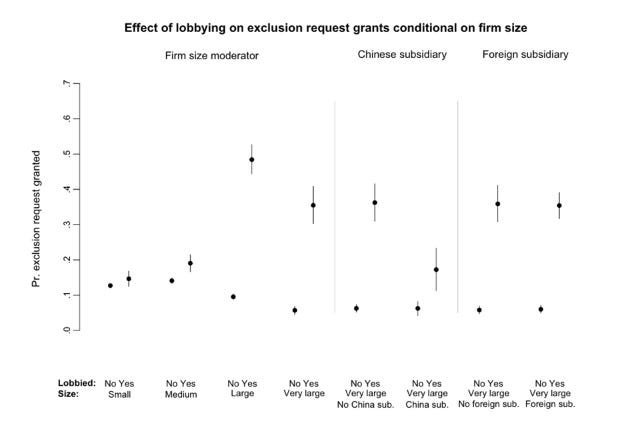

A recent paper by Ayse Eldes (Princeton University), Jieun Lee (University of New York at Buffalo), and Iain Osgood (University of Michigan) finds that lobbying has a strong correlation to tariff exclusion request approvals, but the effect depends oncorporation size and their ties to China. They argue that lobbying works because it draws overburdened policymakers’ scarce attention the economic costs a proposed tariff would impose. When firms lobby, they can provide information policymakersmay not otherwise have about these costs. A willingness to spend money also signals to policymakers that a policy will cause significant harm. The authors suggest that lobbying may be especially effective for larger firms because their economic footprint makes claims of broad economic harm more credible. In contrast, multinational firms often have a smaller domestic impact, providing a less persuasive case for exclusion and resulting in fewer approvals. Overall, their results suggest that lobbying may effectively create policy change, but the extent to which this is true depends on company characteristics.

In order to investigate lobbying’s effectiveness, the authors first examined whether firms that lobbied on the Section 301 tariff exclusion process, measured using public lobbying reports available through opensecrets.org, were more likely to earn an exclusion from the USTR. Secondly, they accessed whether the positive effect of lobbying on securing desired policy outcomes is less pronounced for companies that own subsidiaries in China. Lastly, they tested whether lobbying is more effective for large companies.

Using data from over 52,746 exclusion requests, the team’s analysis revealed that lobbying on the Section 301 tariffs had a highly robust, positive effect on the likelihood of earning exclusion. On average, firms that lobbied the USTR increased their chance of earning exclusion somewhere between 10% and 16%. Since only 13% of exclusion requests were approved, these are significant relative effects. Even so, the study revealed stark inequalities in lobbying’s effectiveness. It concluded that large firms were much more likely to successfully earn exclusions. In contrast, small and medium-sized firms saw very little success. Also, in line with expectations, the results show that companies with Chinese subsidiaries saw significantly less success in their attempts to gain exclusions. This result was seen even among the largest multinational corporations.

In effect, the tariff exclusion process was tough on business who were outsourcing work to China, but softened the blow for larger, well-resourced, economically significant players. Their findings have implications that reach even beyond the China - America trade war. The link between corporation size and their ability to obtain tariff exclusions is an example of how the American status quo operates: As protectionism increases, we see the biggest beneficiaries are still the largest corporations over smaller firms. This study helps to show a clear link between lobbying and policy outcomes in the United States, demonstrating how lobbying can be used to uphold existing hierarchies.

Grossman, Gene M., and Elhanan Helpman. Protection for Sale. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1994.

Lee, Jong-Hyun, and Kyu Baik. “Corporate Lobbying and Antidumping Duties.” Journal of International Economics, vol. 82, no. 1, 2010, pp. 123–135.