Who Bore the Brunt? Mapping America’s Uneven Exposure to the China Shock

A state-by-state look at how Chinese imports reshaped American jobs and industries

The early 2000s brought an economic jolt that reshaped entire regions: factories shuttered, wages stagnated, and long-standing businesses disappeared almost overnight. Communities built on manufacturing were suddenly exposed to a tidal wave of cheap imports, driven by China’s rapid industrial rise. At the time, policymakers welcomed China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization (WTO) with optimism, expecting economic integration to open new markets and anchor China in global norms. Instead, it set off one of the most disruptive trade realignments in modern U.S. history. Between 2001 and 2015, U.S. imports from China more than quadrupled, surging from $102.3 billion to $483.2 billion.1

The China Shock’s consequences continue to shape both economic policy and political debate. Much of the ongoing reassessment stems from the influential work of economists David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson, whose landmark 2013 paper revealed the deep and uneven labor market effects of Chinese import competition. Their study found that regions most exposed to surging imports, particularly those that specialized in furniture, textiles, and electronics manufacturing, experienced sharp employment losses, declining wages, and increased reliance on social safety nets.2 Their findings sparked a broad wave of analysis, critique, and reflection.3 Further research by Autor and coauthors found that many regions eventually recovered from the China Shock; however, the original displaced manufacturing workers largely did not.4 Their work is accompanied by a plethora of research focusing on the costs and benefits of free trade with China, such as job losses, employment gains and wage growth in non-manufacturing sectors.5

A recent New York Times op-ed, “We Warned About the First China Shock. The Next One Will Be Worse,”6 further emphasizes that the discussion around free trade and American manufacturing remains far from settled. Collectively, these works reflect a growing awareness that the long-promised benefits of globalization came at far higher domestic costs than many had anticipated.

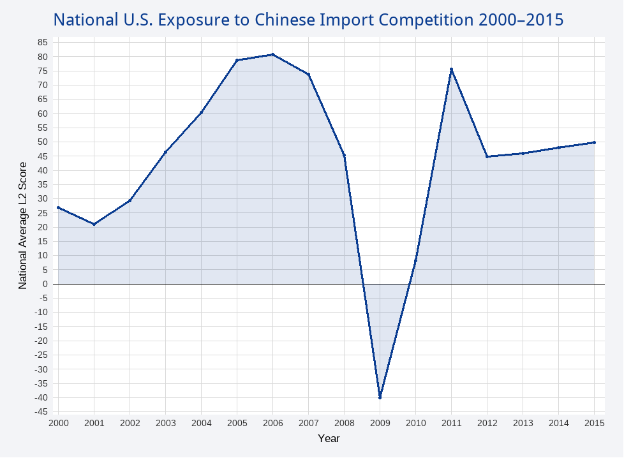

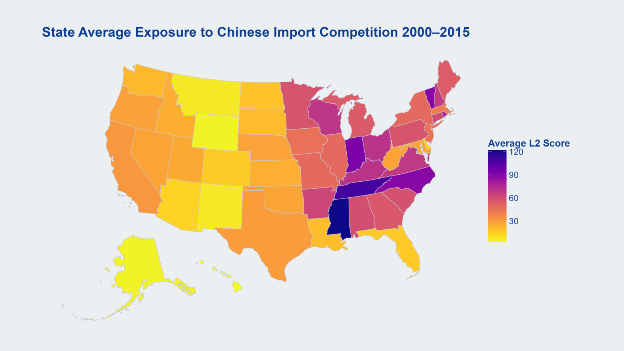

Understanding how this shock reverberated across different states requires a more granular lens than national trade balances. A dataset developed by political economists James Bisbee and B. Peter Rosendorff provides just that.7 By analyzing labor market exposure to Chinese imports alongside job immobility -- the difficulty workers face switching to new occupations -- Bisbee and Rosendorff develop a nuanced framework displaying the vulnerability of American workers. This framework focuses on two main indicators: a two-year lag (L2), which captures short-term labor market disruptions stemming from recent trade exposure, and a five-year lag (L5), which reflects more persistent, structural impacts as industries and communities adjusted or failed to adjust. Anticipatory variables were used to confirm that rising job insecurity came from import pressure, not preemptive worker behavior.

Both the L2 and L5 variables visualize the ground level reality for workers by quantifying how susceptible their industry was to import competition and their difficulty in finding alternative work. The L2 focuses on commuter zones, groupings of nearby communities where people live and work. Whereas the L5 metric uses the sum of all county level data to build an overall picture for the state.

Nationwide trends underscore the volatility of the period. From a pre-WTO baseline average exposure of 26.9 in 2000, the L2 score surged to 80.8 by 2006, reflecting the full force of China's integration into global markets. Even the large-scale trade disruption brought on by the 2008 recession and subsequent plummeting of the 2009 L2 score to -40.0 failed to stymy competition for American manufacturing workers. This long-term, systemic effect is further supported by the L5 metric, which remained elevated during the recession, highlighting how deeply embedded the damages of Chinese import competition had become. By 2011, L2 exposure had rebounded sharply to 75.5 before ultimately stabilizing at an average of 47.1 from 2012-2015, well above the 26.9 pre-WTO baseline. The data tells a clear story: the China Shock was not merely a flashpoint but a long-term transformation in the structure of American manufacturing. Workers displaced by Chinese imports before the recession were often hit again, this time by a collapsing economy and housing foreclosures.

The states most acutely affected were Mississippi, Tennessee, Indiana, Vermont, and North Carolina. These states shared common traits: a reliance on labor-intensive manufacturing sectors, limited worker mobility, and often weaker labor protections. Mississippi, for example, faced high exposure due to its dependence on furniture and textile industries, while Tennessee and Indiana grappled with upheaval in automotive and machinery production. Vermont, less frequently highlighted in national conversations, suffered due to its niche electronics and components sector, which was especially vulnerable to Chinese imports.

By contrast, states like Hawaii, Alaska, Wyoming, Nevada, and Colorado experienced minimal disruption. These states either had diversified service-based economies, a smaller industrial base, or industries less exposed to Chinese competition. While not entirely insulated, their relative immunity highlights how geography, economic structure, and industrial composition mediate the effects of globalization.

The lessons of the China Shock remain critically relevant as the United States enters a new era of industrial transformation. Emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and automation, along with growing global competition in sectors such as semiconductors, electric vehicles, and biotech, pose significant risks to existing job markets. Much like the influx of low-cost imports in the early 2000s, these forces can reshape local economies rapidly and unevenly. While the appropriate response will depend on regional context and expertise, the lasting consequences of the China Shock make one point clear: it is less costly to anticipate disruption than to respond to it after it has occurred. Retroactive policies like tariffs fight an old battle, one that has already passed. It is imperative that policies are targeted and forward thinking, designed for our ever-evolving world. Policymakers, researchers, and local leaders must remain alert to the early signs of structural change and stay focused on the communities most vulnerable to economic upheaval.

“Growth in U.S.–China Trade Deficit between 2001 and 2015 Cost 3.4 Million Jobs: Here’s How to Rebalance Trade and Rebuild American Manufacturing.” Economic Policy Institute, 2015, www.epi.org/publication/growth-in-u-s-china-trade-deficit-between-2001-and-2015-cost-3-4-million-jobs-heres-how-to-rebalance-trade-and-rebuild-american-manufacturing/?utm_source=chatgpt.com. Accessed 28 July 2025.

Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. "The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States." American Economic Review 103 (6): 2121–68. DOI: 10.1257/aer.103.6.2121

Massocco, Ilaria. “The China Shock: Reevaluating the Debate.” Big Data China, 14 Oct. 2022, bigdatachina.csis.org/the-china-shock-reevaluating-the-debate/.

Autor, David, et al. “Places versus People: The Ins and Outs of Labor Market Adjustment to Globalization.” NBER, 3 Feb. 2025, www.nber.org/papers/w33424, https://doi.org/10.3386/w33424.

Autor, David, et al. “On the Persistence of the China Shock.” National Bureau of Economic Research, 1 Oct. 2021, www.nber.org/papers/w29401. ; Bloom, Nicholas, et al. The China Shock Revisited: Job Reallocation and Industry Switching in U.S. Labor Markets. 1 Nov. 2024, www.nber.org/papers/w33098, https://doi.org/10.3386/w33098. ; Wang, Zhi, et al. “Re-Examining the Effects of Trading with China on Local Labor Markets: A Supply Chain Perspective.” National Bureau of Economic Research, 1 Aug. 2018, www.nber.org/papers/w24886.

Autor, David, and Gordon Hanson. “Opinion | We Warned about the First China Shock. The next One Will Be Worse.” The New York Times, 14 July 2025, www.nytimes.com/2025/07/14/opinion/china-shock-economy-manufacturing.html.

Bisbee, James, and B. Peter Rosendorff. “Antiglobalization Sentiment: Exposure and Immobility.” American Journal of Political Science, 16 June 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12872. Accessed 29 Oct. 2024.