Why America’s Businesses Bit Their Tongues on Tariffs

Political loyalty, not profit margins, drove firms’ surprising silence during Trump’s trade war

For decades, the private sector has remained largely unanimous about the benefits of free trade. Outside of specialized manufacturing industries, such as steel and aluminum, American firms have publicly and privately pushed for greater economic liberalization. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce, one of the largest lobbying associations in the United States, continues to argue that “trade means growth for America.” Yet when President Trump launched his first trade war with China in 2018, the response from the private sector was puzzlingly muted. Despite economists estimating that these trade policies cost U.S. consumers and businesses roughly $4.6 billion per month, with $165 billion worth of trade redirected to avoid tariffs1, self-interest did not drive the very corporations and individuals with the most at stake to intervene.

According to a recent paper2 by Lindsay Dolan (Wesleyan University), Robert Kubinec (University of South Carolina), Daniel Nielson (University of Texas – Austin), and Jack Zhang (University of Kansas)2 this lack of action is not caused by ignorance of tariffs’ negative impacts. Instead, firm opposition to tariffs is determined by the company’s political culture, regardless of their effect on their bottom-line. This disconnect between economic harm and political inaction complicates long-held assumptions about how firms behave in response to hostile policy, raising broader questions about the extent to which rational self-interest can explain politics a polarized era.

To investigate the issue, researchers began with a straightforward theory: perhaps America’s small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) were silent simply because they lacked adequate information. Because tariff costs often hit indirectly through supply chains, managers might not realize the true financial ramifications. The team conducted a survey experiment with more than 1,200 U.S. business managers. A treatment group received industry-specific tariff-cost estimates, while a control group did not. All participants were then offered six concrete ways to act politically, such as signing a petition or contacting their member of Congress, and their engagement was tracked.

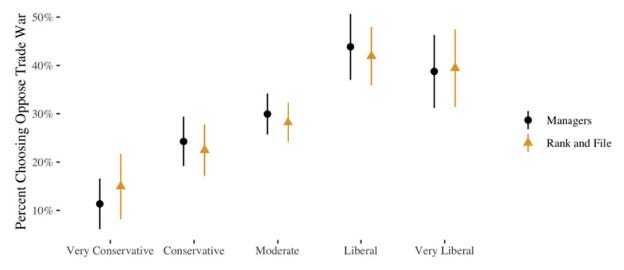

The evidence, however, did not support the information-deficit theory. Managers who received cost data showed no statistically significant uptick in political engagement; in fact, the treatment slightly reduced the likelihood of congressional contact. Instead, a firm’s political culture proved decisive: managers at very conservative firms had only a ten-percent probability of opposing the tariffs, forty points lower than their liberal counterparts.

In an atmosphere of extreme political polarization, ideology may indeed eclipse profit margins themselves. Rather than acting as purely pragmatic organizations, America’s small businesses seem to function as living and breathing collections of like-minded voters, aligning their policy preferences with partisan identity. Reactions to tariff policies, then, may reflect broader ideological commitments rather than traditional cost-benefit calculations. This suggests that polarization may be producing a disconnect between political preferences and fiscal reality.

Amiti, Mary, Stephen J. Redding, and David E. Weinstein. 2019.“The impact of the 2018 tariffs on prices and welfare.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 33: 187–210

Dolan LR, Kubinec RM, Nielson DL, Zhang JJ. Tariffs and corporate political activity: a survey experiment on US businesses. Business and Politics. Published online 2025:1-22. doi:10.1017/bap.2024.41