Why Farmers Kept Planting Crops China Wouldn’t Buy

How partisan loyalty shaped farmers’ planting decisions during the U.S.–China trade war.

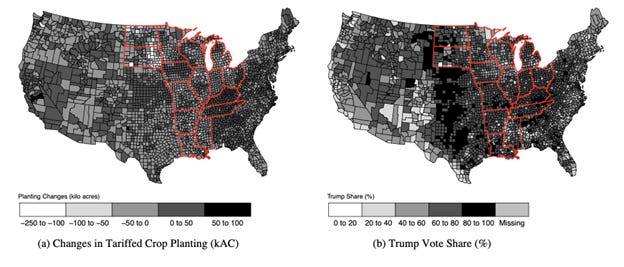

During Trump’s first trade war (2018-2020), U.S. tariffs on China soared. In response, China imposed tariffs on American crops such as soybeans. U.S. Agricultural exports to China were cut in half and, with fewer buyers, prices fell. As a result, many farmers, facing economic losses, instinctively chose to grow different crops; however, some did not. Why did nearly half of U.S. counties actually plant more of the very crops China targeted?

A recent paper from Shannon Carcelli (University of Maryland) and Kee Hyun Park (University of Arizona) analyzes how partisanship – particularly support for Donald Trump – influenced farmers’ decisions. The authors argue that farmers in pro-Trump counties continued planting tariffed crops because they trusted Trump’s public statements that the trade war would end soon and prices would quickly rebound. The implications are significant: Even in high-stakes economic environments such as agriculture, elite cues can override economic logic.

Carcelli and Park’s key finding was that counties that voted for Trump by a wider margin planted more tariffed crops. The authors used data from the USDA’s cropland data layer1 as well as Chinese tariff lists and the 2016 Trump vote share by county to find that a 1% increase in Trump vote share produced a 100-213 acre increase in growing tariffed crops—especially soybeans—planted in 2019. In counties with high Trump support such as Wayne County, Illinois, Carcelli and Park found that farmers planted up to 10,000 more soybean acres than demographically similar Democratic counties. This suggests that elite cues from Trump shaped planting decisions, contradicting traditional economic models that predict farmers act only on market signals.

The Trump administration attempted to counter the Chinese tariffs on agricultural goods with subsidies via the Market Facilitation Program (MFP). Farmers could have planted tariffed crops in anticipation of subsidies. However, when Carcelli and Park accounted for these subsidies in their models, Trump support still predicted planting behavior. Further analysis showed that subsidies did not significantly change the effect of political support on crop choices.

Another alternative explanation is that farmers were “signaling” partisan identity by planting these crops, sort of like a political sign on your front yard. To test this theory, Carcelli and Park replaced Trump 2016 vote shares with Republican vote share in the 2018 House elections as the main predictor of planting tariffed crops. If planting behavior was about partisan signaling rather than elite cues from the Trump administration, then Republican vote share in 2018 should be an equally good predictor as Trump’s vote share in 2016. This variable turned out to have no significant effect on planting behavior. This, in turn, suggests that planting behavior is driven by elite cues rather than performance of partisan identity.

Overall, Carcelli and Park show that partisan loyalty to President Trump led many farmers to continue financially harmful planting behavior during the US-China trade war. These findings challenge the idea that business behavior is purely driven by rational self interest. Farmers use vast amounts of information and regularly monitor the market to make informed decisions, but they are swayed by partisan trust, demonstrating that polarization affects economic decisions. In highly polarized environments, political support can outweigh rational decision making.

Read more:

Soybean planting levels